Plenty of fish in the sea but for how long? The role Earth observation satellites play in the fight against illegal, unreported or unregulated fishing

6 min.

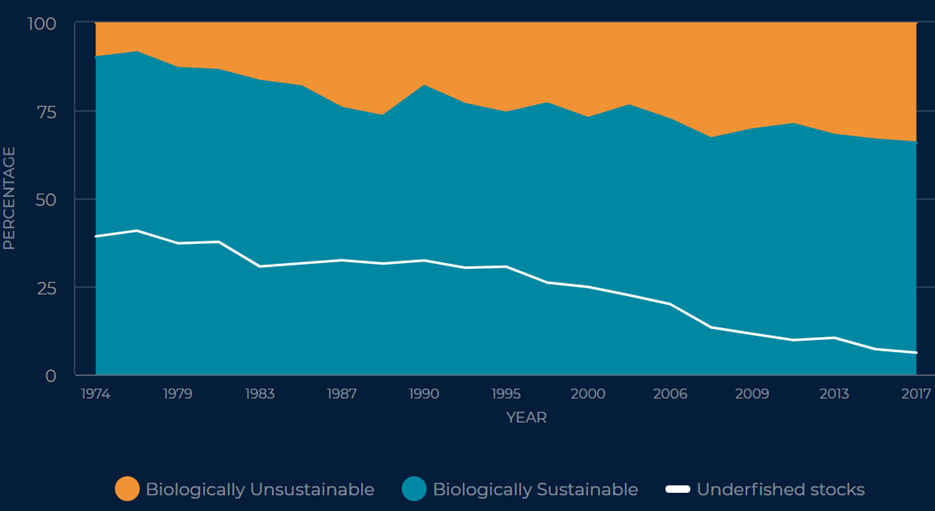

The global annual catch has reached 156 billion tons of fish, the largest in history, a direct result of an industry employing approx. 40 million people worldwide. With a spectrum of operators varying from companies owning fishing vessels worth millions to self-sustaining individuals clearly incentives to break regulations are quite common when focusing on a bigger catch.

Regulations and initiatives were put in place in an effort to fight extensive fishing and its corrosive effects on biodiversity, the result of an overexploitation of a variety of fish stocks worldwide. Illegal, unreported, or unregulated (IUU) fishing is a transboundary matter significantly impacting legality, biodiversity and even human rights. IUU fishing takes various forms – fishing using foreign ships in another country’s waters, falsifying catch reports, using prohibited gear, harvesting protected species, fishing in closed-off areas or off-seasons, abusing distance water fishing, etc. Due to its illicit and clandestine nature, the financial repercussions of this phenomenon are difficult to estimate being assumed to be around 10-20 billion euros per year. It is also estimated that a quarter of the commercialised fish is IUU.

This is not to say that IUU affects all countries equally, the most vulnerable communities being in fact those highly dependent on fishing as main source of labour (and of protein). This is notably an issue in developing countries where law enforcement is problematic and corruption thrives. In these particular cases, IUU fishing can often be correlated with other criminal activities, such as drug smuggling, human trafficking and forced labour, slavery and financing terrorist activities.

Despite the intense regulatory efforts – the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982), down to the numerous local, regional and international laws (e.g. the EU’s IUU Regulation aimed at preventing, deterring and eliminating the commercialisation of IUU-resulting products within the EU by working alongside countries considered uncooperative in the fight against IUU) – IUU remains an unresolved global issue. While necessary, regulations have often resulted to be difficult to implement for various reasons: be these scarce monitoring and implementing resources, political instability or even the mundane challenge of monitoring vessels within one’s own exclusive economic zone (EEZ) or the high seas.

What is the role of Earth observation?

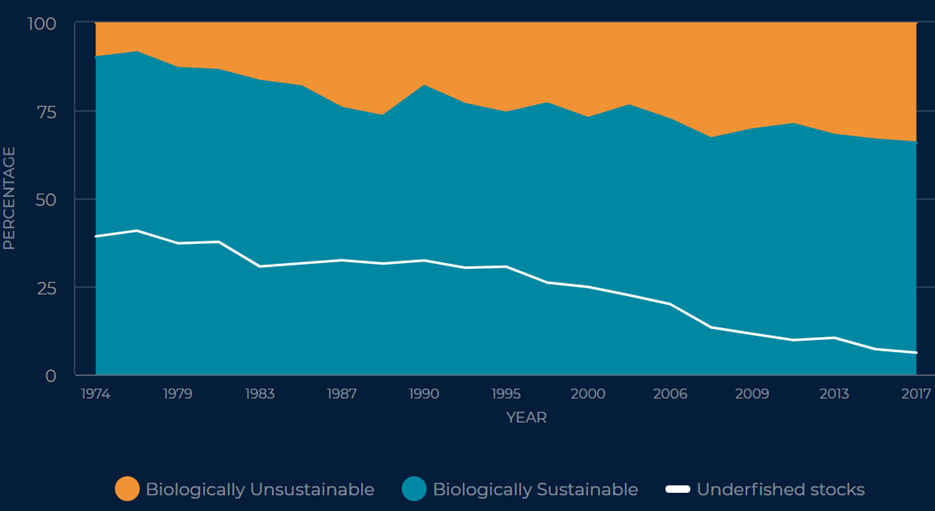

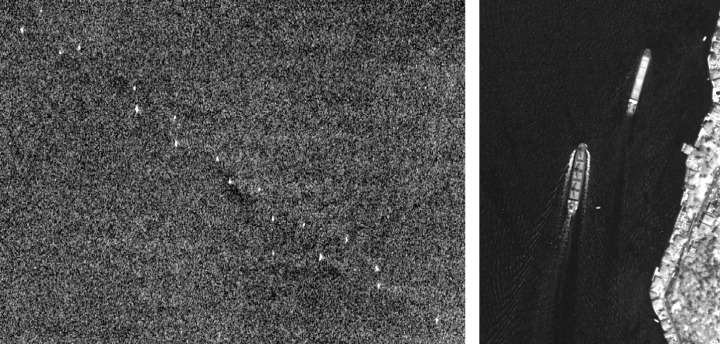

The satellites used for Earth observation (EO) purposes have long been providing data and monitoring solutions for fisheries. In the 70s, data captured by meteorological satellites was first used to detect vessels by the light they emitted – although, at the time, use remained limited due to the low spatial and temporal resolution available. Nowadays, remote sensing is uniquely positioned to assist with the identification, detection and tracking of vessels (IUU, oil spills, etc.) particularly when these choose to “go dark” making themselves unidentifiable by turning off their location transmitters – Automatic Identification System (AIS), Vessel Monitoring System (VMS), etc.

The developed solutions exploit radar and/or optical technologies, with synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) being particularly used as, unlike optical, SAR imagery is not dependent on weather, cloud cover, or daylight. The uptake of optical imagery for similar purposes has increased recently as has the availability of high-resolution and very-high-resolution data which enables the identification of smaller than before vessels. Currently, some commercial solutions, both optical and SAR, offer spatial resolutions of 50cm x 50cm.

Who provides the data? Authorities, NGOs, private companies, and research projects.

Since compliance enforcement mainly resides with the local authorities, the main users and providers of EO data for IUU are the authorities themselves. Such matters have long been handled by NOAA in the United States whereas Canada has only recently launched a dedicated EO-based IUU tracking program. In Europe, Copernicus Maritime Surveillance (CMS) provides Security Services EO products (satellite images and value added services) exploiting the EU’s Copernicus Programme for a better understanding and improved monitoring of activities at sea. CMS is implemented by the European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) and offers support to the European Fisheries Control Agency (EFCA) and to the relevant Member State administrations by providing satellite monitoring over the EU, third countries and the international waters. The support consists of:

The satellite images acquired by CMS are correlated with location data sets resulting in vessel detection and identification reports made readily available for consultation to the end user.

Driven by an increased awareness of the practices and consequences of IUU fishing, NGOs have also stepped up their contribution to the fight. The Global fishing watch initiative’s map is the first dynamic, global, near real-time and openly accessible window on the fishing activity. The platform’s algorithm brings together AIS and VMS data, satellite technology, cloud computing and machine learning. The satellite data it uses comes from various sources: space agencies and commercial providers.

In June 2021, Oceana’s IUU Vessel Tracker – which the NGO had built based on data from the Global fishing watch – showed in real time a potentially abusive and widespread switching-off of AIS capabilities among presumed IUU vessels in an effort to increase transparent practices in the fisheries sector.

SAR and optical technological advancements have rendered private companies increasingly competitive when it comes to providing high and very-high resolution data. SAR innovators, such as ICEYE and Capella Space, are flying their own constellations with the former already offering a solution that combines their SAR data with AIS data. Thus, the race for reliable vessel identification seems to have just started.

Last but not least, research projects are also progressing the work necessary for vessel identification related to fisheries. Pilot 5.5 in e-shape makes use of satellite data (EO, as well as AIS communication data) to monitor fishing activities potentially for MSFD reporting regarding the anthropogenic pressure indicator.

Its outcome is a web-based tool disseminating geo-referenced information focused on:

The pilot focuses on tuna and sword fish within the Portuguese EEZ, but once developed the product could be extended to other species.

What is next?

Overfishing is far from being a simple issue. The many interests at play have severe and negative consequences on biodiversity, the local and world economies, and even on other illegal activities. As the growth of the fishing industry is not expected to slow down any time soon, immediate action against IUU fishing is required. As a society, we are now better equipped to take action against such practices thanks to the available regulatory tools and monitoring solutions – such as Earth observation (and many others!), there to assist us towards achieving sustainability. It is therefore our responsibility to make the best use of them.